In the Park

Glenn Walls. (Death and Dancing) In the Park. 2024. Alvar Aalto, Stool 60, 1933, Gay flag, Stencil, Yellow Paint. Contains an image of the painting, “Two dancing male figures in a landscape”. Anonymous, French, 18th Century. The Met Fifth Avenue. Installation view.

Glenn Walls. (Death and Dancing) In the Park. 2024. White paper stack, Yellow Paint. Contains an image of Ross Warren who was one of the victims of the gay killing spree that took place in Sydney in the late 20th Century. Ross Warren is suspected of being murdered on 22nd July 1989.

Glenn Walls. (Death and Dancing) In the Park. 2024. Alvar Aalto, Stool 60, 1933, Contains an image of Scott Johnson who was murdered on the 8th December 1988 in Manly.

Glenn Walls. (Death and Dancing) In the Park. 2024. Alvar Aalto, Stool 60, 1933, Gay flag, Stencil. Contains an image of the painting, “Two dancing male figures in a landscape”. Anonymous, French, 18th Century. The Met Fifth Avenue. Installation view.

Artist Statement

Between the 1970s and early 2000s, before queer visibility came to the fore in Sydney, Australia, many gender and sexual non-normative people living under the conditions of heteropatriarchy managed to develop different ways of interacting with others at queer sites and spaces. Unintelligible in the mainstream cultural imagination, these practices of communication and connection were a means of survival that enabled queer life to flourish. However, when the location of these queer sites became known to certain other social groups, they became epicentres of catastrophic violence, linked to 88 murders. The works developed for “In the Park” explore how gender and non-normative people gravitated to Sydney to create new identities and communities making them the target of stigmatization and violence by a small minority. The artworks argue for the legitimacy of queer life, revealing the extent of violence perpetrated against the LGBTQI+ community. I hope to contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the historical and spatial dimensions of violence against the LGBTQI+ community and advocate for its more nuanced portrayal in contemporary narratives. By harnessing the language of modernist furniture and maps which created a sense of clean, clinical space free of interpretation, these artworks contest dominant views of modernist design and humanise modernist/minimalist theory and practice to obscure its problematic relationship to identity and sexuality.

Losing my Religion

Glenn Walls. That’s me in the corner. That’s me in the spotlight. Losing my Religion. Digital print. 2023. Shot on location at the Vatican, Rome. July 2023.

Words taken from R.E.M song ‘Losing my Religion’. Released 1991.

Glenn Walls. That’s me in the corner. That’s me in the spotlight. Losing my Religion. Digital print. 2023. Shot on location at the Vatican, Rome. July 2023.

Words taken from R.E.M song ‘Losing my Religion’. Released 1991.

Comments Off on Losing my Religion

Super Play

Glenn Walls. Super Play. Mirror tiles, skateboard wheels, swing. 2023. This sculpture is based on Superstudio “The Continous Monument” 1969 – 71. Imagined in the TATE Modern Turbine Hall. London.

Glenn Walls. Super Play. Mirror tiles, skateboard wheels, swing. 2023. This sculpture is based on Superstudio “The Continous Monument” 1969 – 71.

Comments Off on Super Play

Forever Young. Installation view.

Glenn Walls. Untitled (Take a look at the law man beating up the wrong guy). Metal plate, paper stack. 2022. Words are taken from David Bowie’s 1971 – 73 song “Life on Mars”.

Comments Off on Forever Young. Installation view.

Untitled (Forever Young, The Smiths). There is a light that never goes out. Installation View.

Glenn Walls. Untitled (Forever Young, The Smiths). Mirror tiles, laser cut metal, gold beads, 2022. Words are taken from The Smiths’ 1985 song “There is a light that never goes out”.

Comments Off on Untitled (Forever Young, The Smiths). There is a light that never goes out. Installation View.

It’s the End of the World as We Know It (and I Feel Fine).

Glenn Walls. Untitled (It’s The End of the World as We Know It, and I Feel Fine). 2023. Digital Print. Photographed on location at P.za Cavour, Rione Sanita, Naples, Italy, July 2023. Text from the 1987 REM song, ‘It’s The End of the World as We Know It (and I Feel Fine).

Glenn Walls. Untitled (It’s The End of the World as We Know It, and I Feel Fine). 2023. Digital Print. Photographed on location at P.za Cavour, Rione Sanita, Naples, Italy, July 2023. Text from the 1987 REM song, ‘It’s The End of the World as We Know It (and I Feel Fine).

Everybody Hurts

Glenn Walls. Untitled (Everybody Hurts, Sometimes). 2023. Digital Print. Photographed on location at the Neue Nationalgalerie, Berlin, January 2022. Designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe in 1968. Words from the 1992 REM song ‘Everybody Hurts’.

Comments Off on Everybody Hurts

The Modern World – Berlin

Glenn Walls. Untitled (Am I ever going to see your face again). 2023. Digital Print. Photographed on location at the Neue Nationalgalerie, Berlin, July 2023. Designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe in 1968. Text from the 1977 song, ‘Am I Ever Gonna See Your Face Again’ by Australian band The Angels.

Glenn Walls. Untitled (Me). 2023. Digital Print. Photographed on location in Berlin, July 2023.

Glenn Walls. Untitled (Meth is a big thing here. Meth and Modernism). 2023. Digital Print. Photographed on location at the Neue Nationalgalerie, Berlin, January 2023. Designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe in 1968. Text from the 2017 film ‘Columbus’ set in Columbus, Indiana, USA.

Comments Off on The Modern World – Berlin

THE AUSTRALIAN UGLINESS

Glenn Walls. Cover of Robin Boyd’s book ‘The Australian Ugliness’. First published in 1960.

Original cover drawing by Robin Boyd. Reimagined in 2023.

Glenn Walls. Super rainbow. Mirror tiles, neon light, skate wheels and mirror plinth. 2023

Glenn Walls. Super rainbow. Mirror tiles, neon light and skate wheels. 2023. Based on the Italian architectural

group, Superstudio’s work, The Continuous Monument: An Architectural Model for Total Urbanisation. 1969 – 71.

Glenn Walls. Robin Boyd, The Australian Ugliness. Chapter 1: The Descent into Chaos. Published in 1960.

The first chapter of Robin Boyd’s 1960 book, The Australian Ugliness. Paper. 2023

Glenn Walls. Robin Boyd, The Australian Ugliness. Chapter 1: The Descent into Chaos. Pg 7. Published in 1960.

Pink eyes stare out for the first glimpse of Australia still filled with an even, empty greyness. Digitally altered. Paper. 2023.

Glenn Walls. Robin Boyd, The Australian Ugliness. Chapter 1: The Descent into Chaos. Pg 8. Published in 1960.

This is the Australian, hard, raw, yet is not malevolent in appearance into the background of Australian life. Its presence cannot be forgotten. Digitally altered. Paper. 2023.

Glenn Walls. Robin Boyd, The Australian Ugliness. Chapter 1: The Descent into Chaos. Pg 9. Published in 1960.

Featurism is by no means confined to Australia. Digitally altered. Paper. 2023.

Glenn Walls. Robin Boyd, The Australian Ugliness. Chapter 1: The Descent into Chaos. Pg 9. Published in 1960.

Featurism is by no means confined to Australia. Paper stacks, A3 in size. Installation view. 2023.

Glenn Walls. Robin Boyd, The Australian Ugliness. Chapter 1: The Descent into Chaos. Pg 10. Published in 1960.

“To hide the truth and camouflage. Camouflage has always been a favoured practice. In Australia. A faint stigma. Veneering has become entirely respectable. Digitally altered. Paper. 2023.

Glenn Walls. Robin Boyd, The Australian Ugliness. Chapter 1: The Descent into Chaos. Pg 11. Published in 1960.

Quotes are taken from ‘Queering the Map’ located in Melbourne. Names and ages are fictional. Digitally altered. Paper. 2023.

https://www.queeringthemap.com/

Glenn Walls. Super rainbow. Mirror tiles, neon light and skate wheels. 2023. Based on the Italian architectural

group, Superstudio’s work, The Continuous Monument: An Architectural Model for Total Urbanisation. 1969 – 71.

Robin Boyd, The Australian Ugliness. Published in 1960.

The Australian Ugliness by Glenn Walls.

Australian architect and architectural critic Robin Boyd’s seminal critique on Australian suburban life and architecture The Australian Ugliness was first published in 1960. In the book, Boyd highlighted Australian architecture’s need to mask its true identity with kitsch materials and imported architectural styles unsuited to the Australian climate and landscape. Boyd referred to this phenomenon as “featurism”. As Emma Letizia Jones states:

“Boyd rejected outright the pervasive signs of a commercial kitsch architectural currency he labelled “Featurism”, and it was characterised by veneers of all sorts: brick veneer construction in the suburbs, brightly coloured plastic veneers in the home, veneers of advertising in the streets, veneers of “Australian character” on an international Western culture. Against this imported Featurism worn as a prettifying mask, Boyd argued for a truly Australian Modern beyond mere cosmetic effects, which he sought through his own architectural projects” (Jones 2014)

Featurism provided architects and builders the opportunity to ‘cover up’ the true identity of a building making it appear as something it was not.

Robin Boyd, The Australian Ugliness. Contents page. Published in 1960.

But this was a period when masking was all the rage, not just in architecture. As Emma Letizia Jones also states, “Featurism in short was the adopted visual style of an ambivalent, uncertain population at odds with its surroundings, unsure of how to inhabit them, clinging to the edges of a continent and looking everywhere for answers but into its own interior” (Jones 2014 p. 96). The post-war era of the 1950s and 1960s was a period of extreme conservatism in Australia. This period coincided with conservative social and cultural attitudes to sexuality and identity. To survive many LGBTQI+ people felt the need to mask their identity. Rachel Morgain highlights the repression and victimisation during this period. She states:

“The years following the Second World War saw a drive to consolidate the family, encourage women to have children and push them out of unconventional war-time jobs, so that there would be positions for returned soldiers. The campaign against homosexuality in the 1950s was an escalation of this process, seeking to rectify the decline in social discipline that conservatives argued had occurred during the war. Over a few years, there was a sharp increase in the number of people charged with and convicted of homosexual offences. Police actively entrapped homosexual men. A special squad targeting homosexuality was set up in the Victorian police and the NSW police superintendent labelled homosexuality ‘the greatest social menace facing Australia’. Homosexuals in the public service became particular targets. There were moves to isolate homosexual men in NSW prisons and to have them locked up in mental institutions. The tabloid press was filled with scandals about gay men. What little coverage there was in the quality press sent a clear message to anyone thinking of straying from the heterosexual norm: that path could lead only to shame and arrest”. (Morgain 2004 p. 5)

Robin Boyd, The Australian Ugliness. Chapter 1: The Descent into Chaos. Pg 7. Published in 1960.

To survive during this period masking by the LGBTQI+ community became a necessity. Certain clothing, hairstyles, and jewellery were to be avoided. Appropriate clothing provided the armour that concealed one’s true identity. Joel Sanders highlights this in the preface to the 2021 reissue of his 1996 book ‘Stud: The Architecture of Masculinity’, “I came to realize that the clothing that clad bodies behaved like the cladding of buildings: wall finishes, paint, fabrics, curtains, upholstery and furniture are like garments, culturally coded applied surfaces that designers use to fashion human identity” (Sanders 2020 p. 8). Similarly, Boyd’s ‘featurism’ that aimed to clad a building in an identity that, according to him was fake, became locations where queer life happened. In this project, I argue that despite the masking of both queer people and architecture, queer identity occurred allowing architecture to become queer space via memory.

By the 1960s bold civil liberties groups and the New York Stonewall Riots in 1969 were seen as a turning point, gay liberation and activism exploded. The LGBTQI+ community began to move out of the fringes and into the mainstream. As laws were repealed, homosexuality decimalised, and attitudes changed our relationship to queer identity and queer space also changed. Boyd’s book The Australian Ugliness provided a snapshot of a particular time in Australia’s cultural and built history, one that was masked in Featurism in search of an identity. But as Peter Conrad states: “Books that quarrel with the way things inevitably lose their point when things change. But it’s no disgrace to re-treat into history, and The Australian Ugliness testifies to a confused and uncertain period in the national life that, with a little help from Boyd, we happily outgrew” (Conrad, p. 63). Sadly, masking one’s identity is still an issue for many in the LGBTQI+ community. To suggest all is well regarding LGBTQI+ rights is an understatement1. However, this project provides the opportunity to engage with queer lives and queer space by marking the location within the pages of Boyd’s book where queer memories occurred and are remembered.

Robin Boyd, The Australian Ugliness. Chapter 1: The Descent into Chaos. Pg 8 & 9. Published in 1960.

Regardless of the featurism found in Australian suburban homes, they were still locations where memories were made. Inspired by artist Tom Phillips’s project ‘A Humument; A Treated Victorian Novel 1966 – 2016, in which Phillips randomly ‘began to doctor the pages with images, both abstract and figurative’ (Kidd, 2012), this project uses the locations found in the text of Boyd book The Australian Ugliness as data points to highlight queer spaces that had the potential for this to occur through fictional recollections, photographs, digital imagery and drawings placed on Boyd text. These are fictional coming-out stories of opportunities that were never recorded but may have happened, but because of the entrenched homophobia and laws in place during this period, a veneer was put in place to mask queer existence in the built environment. With that veneer removed we are now able to engage with locations marked as a place that ‘queer’ happened and remember.

Notes.

1. In the United States of America there have been over 120 Bills Restricting LGBTQ Rights Introduced Nationwide in 2023. Most relate to trans issues. https://www.tracktranslegislation.com/

Bibliography

ABC News 2015, Timeline: 22 years between first and last Australian states decriminalising male homosexuality, ABC News website, accessed 2 February 2023. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2015-08-24/timeline:-australian-states-decriminalise-male-homosexuality/6719702

Australian Human Rights Commission 2023, Face the facts: Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex People, Australian Human Rights Commission website, accessed 2 February 2023. https://humanrights.gov.au/our-work/education/face-facts-lesbian-gay-bisexual-trans-and-intersex-people

Bleakley, P 2021, ‘Fish in a Barrel: Police Targeting of Brisbane’s Ephemeral Gay Spaces in the Pre-Decriminalization Era’, Journal of homosexuality, vol. 68, no. 6, Routledge, United States, pp. 1037–1058.

Boyd, R. (1960). The Australian ugliness. F. W. Cheshire, Melbourne.

Burke, S 2018, Find Yourself in the Queer Version of Google Maps, VICE website, accessed 30 January 2023.

https://www.vice.com/en/article/ne9kjx/queering-the-map-google-maps-lgtbq

Carlson, D 2012, The education of eros: a history of education and the problem of adolescent sexuality, Routledge, New York.

Conrad, P 2009, ‘Coming of Age: Peter Conrad on Robin Boyd’s “The Australian Ugliness” Fifty Years On’, Monthly (Melbourne, Vic.), no. Dec 2009 – Jan 2010, Schwartz Publishing Pty. Ltd, Melbourne, Vic, pp. 60–63.

https://search.informit.org/doi/epdf/10.3316/informit.655309633983791

Dahmubed, C 2018, ‘Memorializing queer space’, Crit, no. 83, pp. 71-78.

Jones, EL 2014, ‘Rediscovering “The Australian Ugliness”. Robin Boyd and the Search for the Australian Modern’, Studii de istoria și teoria arhitecturii, vol. 2014, no. 2, Ion Mincu University of Architecture and Urbanism, pp. 94–114. https://sita.uauim.ro/article/2-jones-rediscovering-the-australian-ugliness

Kidd, J 2012, Every Day of my Life is Like a Page.The Literary Review, Issue 400.Tom Phillips. Accessed 15 February 2023.

https://www.tomphillips.co.uk/humument/essays/item/5858-every-day-of-my-life-is-like-a-page-by-james-kidd

Kontominas, B 2017. ‘Scott Johnson: Inside one brother’s 30-year fight to find the truth’. The Age. Accessed 14 February 2023.

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-11-30/scott-johnson-inside-brothers-fight-to-find-the-truth/9211466

LGBTQI+ Health Australia 2021, Snapshot of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Statistics for LGBTIQ+ People, LGBTQI+ Health Australia website, accessed 2 February 2023. https://www.lgbtiqhealth.org.au/statistics

London Transport Museum 2023, Mapping London: the iconic Tube map. London Transport Museum website, accessed 1 February 2023. https://www.ltmuseum.co.uk/collections/stories/design/mapping-london-iconic-tube-map

Morgain, R. 2004. Sexual liberation: fighting lesbian and gay oppression. Australian National University Publications

https://openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au/handle/1885/42704

National Geographic 2023, Map, National Geographic website, accessed 2 February 2023. https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/map

Oswin, N. (2008) ‘Critical geographies and the uses of sexuality: deconstructing queer space’, Progress in Human Geography, 32(1), pp. 89–103. doi:10.1177/0309132507085213.

Queering the Map. 2023. Queering the Map. https://www.queeringthemap.com/

Sanders, J 2020 (Reissue), Stud: Architectures of Masculinity, Taylor & Francis Group, Milton.

SBS 2016, The history and importance of gay beats, SBS website, accessed 6 February 2023. https://www.sbs.com.au/topics/pride/agenda/article/2016/10/17/history-and-importance-gay-beats

Strike Force Parrabell 2018, New South Wales Police Force. viewed November 11 2022, https://www.police.nsw.gov.au/safety_and_prevention/your_community/working_with_lgbtqia/lgbtqia_accordian/strike_force_parrabell

Wotherspoon, G 2017, Gay Hate Crimes in New South Wales from the 1970s, viewed 11th November 2022, https://www.acon.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/In-Pursuit-of-Truth-and-Justice-Report-FINAL-220518.pdf.

Untitled (Ludwig Mies van der Rohe designed nothing for me)

Untitled (Le Corbusier)

Untitled (Modernist Text Talk)

Glenn Walls. Untitled (You are so cute). 2022. Digital print. Photographed on location at Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, S. R Crown Hall Building, 1956. Illinois Institute of Technology, Chicago.

Glenn Walls. Untitled (I open my mouth and my whole life spills into the driveway). 2022. Digital print. Photographed on location at Richard Neutra, Kaufmann House 1947. Palm Springs, USA.

Glenn Walls. Untitled (I don’t care……). 2022. Digital print. Photographed on location at Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, S. R Crown Hall Building, 1956. Illinois Institute of Technology, Chicago. Lyrics are taken from the Cure 1992 song “Friday I’m in love”.

Untitled (Forever Young, The Smiths). There is a light that never goes out. Detail.

Glenn Walls. Untitled (Forever Young, The Smiths). Mirror tiles, laser cut metal, gold beads, 2022. Words are taken from The Smiths’ 1985 song “There is a light that never goes out”.

Glenn Walls. Untitled (Forever Young, The Smiths). Mirror tiles, laser cut metal, gold beads, 2022. Words are taken from The Smiths’ 1985 song “There is a light that never goes out”.

Glenn Walls. Untitled (Forever Young, The Smiths). Mirror tiles, laser cut metal, gold beads, 2022. Words are taken from The Smiths’ 1985 song “There is a light that never goes out”.

Rationale

Architecture’s preoccupation with ‘normality’ has left little room for queer space to come to the fore. My current practice contributes to the public acknowledgment of queer space in the built environment by highlighting hidden identities. I am interested in creating a personal definition of queer space that is not hidden and is a reaction against normative symbols of masculinity and the ‘heterosexual assumption’ presented by 1960s Italian architectural group Superstudio anti-design grid.

This work extends my practice to encompass a boarder approach to queer space through the placement of text from queer-identifying writers and singers in the built environment. This work aims to highlight how a perceived dominant heterosexual space can be altered to queer space. Utilising the language of Superstudio’s Anti-design grid that overshadow the personal and private needs of the individual I construct narratives, in this case by incorporating the lyrics by perceived queer singer/songwriter Morrisey of The Smiths that adds new layers to Superstudio’s anti-design mirrored grid architecture to imbue it with personal significance.

“And if a double-decker bus crashes into us to die by your side is such a heavenly way to die” is from The Smiths’ 1985 song, “There is a light and it never goes out”.

This work centres on redefining the masculine/heterosexual dominance of modernist structures and spaces via texts and realigns it with a sexual minority.

Comments Off on Untitled (Forever Young, The Smiths). There is a light that never goes out. Detail.

Forever Young Part 2

Glenn Walls. Untitled (Forever Young. Marsha P. Johnson & Harvey Milk). Digital print, wood, mirror perspex, mirror tiles 2022. Words are taken from the 1984 Alphaville song “Forever Young”.

Forever Young is a continuation of the series “Massacre – Bodies that Matter” from 2018 – 2019.

Violence against LGBTQI people continues with the recent shooting inside and outside a gay nightclub in Oslo, Norway in the early hours of Saturday 25th June 2022.

Glenn Walls. Untitled (Superstudio). Painted floor, wood, mirror perspex, mirror tiles 2022. Words are taken from the 1984 Alphaville song “Forever Young”.

Glenn Walls. Untitled (Forever Young). Gold glitter paper 2022. Words are taken from the 1984 Alphaville song “Forever Young”.

Seven Magic Mountains- Ugo Rondinone

Ugo Rondinone. Seven Magic Mountains. 2016. Produced by Nevada Museum of Art and Art Production Fund.

A large-scale desert artwork. Las Vegas, Nevada.

Artist Statement: Seven Magic Mountains is an artwork of thresholds and crossings, of balance marvels and excessive colors, of casting and gathering, and the contrary air between the desert and the city lights.

I have used queer artist Ugo Rondinone boulders from this installation in a number of artworks in recent years. All were photoshopped from photographs from friends. Hence it was with great pleasure that I was able to recently visit Seven Magic Mountains and photograph this incredible installation in the Nevada desert myself. The day we visited the work was a hot 44 Celsius or 111 Fahrenheit. Needless to say, we were unable to spend a huge amount of time in the heat but it was enough to get some great photos of the installation and explore the majestic nature of the sculpture.

Sadly the bases of the seven works had been heavily graffitied. I will never understand why people feel the need to do this. Enjoy.

Forever Young

Violence against LGBTQI people continues with the recent shooting inside and outside a gay nightclub in Oslo, Norway in the early hours of Saturday 25th June 2022

Glenn Walls. Untitled (Take a look at the law man beating up the wrong guy). Metal plate, paper stack. 2022. Words are taken from David Bowie’s 1971 – 73 song “Life on Mars”.

Glenn Walls. Untitled (Forever Young. Marsha P. Johnson). Digital print. 2022. Words are taken from the 1984 Alphaville song “Forever Young”.

Forever Young is a continuation of the series “Massacre – Bodies that Matter” from 2018 – 2019.

Violence against LGBTQI people continues with the recent shooting inside and outside a gay nightclub in Oslo, Norway in the early hours of Saturday 25th June 2022.

More works to follow.

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-06-25/norway-nightclub-shooting-police-possible-terrorism/101183546

Closure

In 2018 I held an exhibition called “Massacre: Bodies that Matter” at Kings ARI. The exhibition highlighted the unsolved gay murders in Sydney in the 1970s to the 2000s. Due to a combination of police indifference/incompetence/homophobia many of these murders went unsolved. Last week the murder of American citizen Scott Johnson was finally solved.

To find out more click on the link below:

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-05-07/scott-johnson-murders-still-haunt-sydney/101045786

To see the works from the 2018 exhibition “Massacre: Bodies that Matter” at Kings ARI.

https://glennwalls.com/category/massacre/

Glenn Walls. Drawing from Butt Magazine. 2018. Drawing on paper. 21 x 20 cms

I never can say goodbye (Part 2)

Glenn Walls. At the end of the day, people are just really disappointing. Black sequin material, mirror perspex letters, white frame 2021.

Glenn Walls. Remember the future is not yet written. Black sequin material, mirror perspex text, white frame 2021.

Glenn Walls. “If you are not too long, I will wait here for you all my life”. Quote from Oscar Wilde. Mirror ball, black sequin material, and mirror perspex text.

Glenn Walls. “If you are not too long, I will wait here for you all my life”. Quote from Oscar Wilde. Mirror ball, black sequin material, and mirror perspex text. Detail.

Architecture preoccupation with ‘normality’ has left little room for queer domestic space to come to the fore. This body of work contributes to public acknowledgment of queer space in the built environment, highlighting queer injustices. Few artists have broached this subject. I am interested in creating a personal definition of queer space that is not hidden and is a reaction against normative symbols of masculinity and the ‘heterosexual assumption’ presented by 1960s Italian architectural group Superstudio anti-design grid. Inspired by Cuban artist Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s work “Untitled” (Death by Gun), 1990, these works are based on research conducted on the gay and trans killings that took place in Sydney and worldwide in the late 1970s till now.

I never can say goodbye

Glenn Walls. I never can say goodbye. Wood board, laser cut mirrored letters, sequin material. 2021. Words are from the Gloria Gaynor song. “Never can say goodbye”, 1974.

Glenn Walls. I never can say goodbye (After Felix). Digital print, paper stack. 2021. This work contains an image of American LGBTQI rights activist Marsha P. Johnson who was murdered in 1992.

Glenn Walls. I never can say goodbye (After Felix). Digital print, paper stack. 2021. This work contains an image of Superstudio -Supersurface, 1971.

Glenn Walls. I never can say goodbye (After Felix). Digital print, mirror ball, paper stack. 2021. Text on the mirror ball is a quote from Oscar Wilde, “If you are not too long, I will wait here for you all my life”. This work contains an image of Ross Warren who was murdered in July 1989 at the Bondi headlands, a well know gay beat.

Glenn Walls. I never can say goodbye. Mirror tiles, mirror plinth, skateboard wheels, red sequin, 2021. Based on Superstaudio, “Continuous Monument”, 1969.

Glenn Walls. I never can say goodbye. Mirror tiles, mirror plinth, skateboard wheels, red sequin, 2021. Based on Superstaudio, “Continuous Monument”, 1969.

Architecture’s preoccupation with ‘normality’ has left little room for queer domestic space to come to the fore. This body of work contributes to public acknowledgment of queer space in the built environment, highlighting queer injustices. Few artists have broached this subject. I am interested in creating a personal definition of queer space that is not hidden and is a reaction against normative symbols of masculinity and the ‘heterosexual assumption’ presented by 1960s Italian architectural group Superstudio anti-design grid. Inspired by Cuban artist Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s work “Untitled” (Death by Gun), 1990, these works are based on research conducted on the gay and trans killings that took place in Sydney and worldwide in the late 1970s till now.

“I can never say goodbye Part 1 & 2” is a continuation of research conducted from the 2018 exhibition “Massacre: Bodies that matter” held at Kings ARI, which is found further down on this website.

The text below is from “Massacre: Bodies that matter”.

‘Our blood runs in the streets and in the parks and in casualty and in the morgue…. ‘Our own blood, the blood of our brothers and sisters, has been spilt too often….

‘Our blood runs because in this country our political, educational, legal and religious systems actively encourage violence against us…

‘We are gay men and lesbians.’

From the ‘One in Seven’ Manifesto, Sydney Star Observer, 5 April 1991

During the 1970s, 80s & 90s in Sydney, Australia a high number of LGBTIQ people were violently bashed, murdered or disappeared entirely. Although some of these incidents were reported in the gay press and the NSW Anti-Discrimination Board[1] at the time many remained unreported to the authorities[2] due to cultural and societal attitudes with and within the NSW police force and the wider community tolerance of homosexuality. With the advent of AIDS in the 80s, “a significant media and social response of gay alienation within the context of ‘moral panic’ occurred” (Strike Force Parrabell 2018, p. 13). ‘Beats’ such as toilet blocks, public parks and beaches (Bondi Headlands) where men met other men for sex or social contact became the target of gangs that felt it was their duty to rid and protect the community of such ‘intolerable’ behaviour [3].

By the late 90s, early 2000s with a growing acceptance within the wider community of homosexuality a series of media reports and research papers emerged within the mainstream press highlighting both the injustice caused to the LGBTIQ community and the entrenched homophobia and failure within the NSW police force that allowed a ‘killing and bashing spree” to take place with little repercussion to the perpetrators[4].

American Ph.D. candidate Scott Johnston was only 27 when he died. “It was December 10, 1988, when Scott’s naked body was found by two rock fishermen at the base of the cliff, near Blue Fish Point, just south of Manly, on Sydney’s northern beaches. Scott’s clothes had been found neatly folded on the clifftop above” (Kontominas 2017) including his pair of Adidas sneakers. This is shown in the exhibition as a wood carving. The police deemed it a suicide. Three months later, Coroner Derrick Hand came to the same conclusion. His brother Steve Johnson and boyfriend of five years, Michael Noone is still today not convinced that this is the case. All failed to acknowledge that the location was a well know beat where anti-gay gangs operated and where other gay/hate murders had occurred previously.

The main research question addressed in this exhibition is:

Through sculptures, architectural models, and digital prints, in what ways can I reconfigure the masculine/heterosexual dominance of Superstudio’s anti-design grid to a personal interpretation of queer space?

My reading and understanding of this grid argue a social, philosophical, and identity position in which to interpret my works, giving the audience a greater understanding of the power of things to form a narrative for the object or space. My aim is to think through these processes via practice, critiquing Superstudio’s anti-design grid to produce work that re-evaluates masculine/heterosexual dominance of architectural space by highlighting an injustice done to a minority.

Research contribution

Architecture’s preoccupation with ‘normality’ has left little room for queer domestic space to come to the fore. I argue that ‘the “normality” of heterosexuality is so deeply ingrained in Western culture that it is not even seen’ (Myslik 1996, p. 159). So entrenched is this understanding that I have found little evidence of the public acknowledgment of queer space in the built environment, let alone one highlighting queer injustices. Few artists have broached this subject. I am interested in creating a personal definition of queer space that was not hidden and is a reaction against normative symbols of masculinity and the ‘heterosexual assumption’ presented by Superstudio anti-design grid.

Inspired by Cuban artist Felix Gonzalez-Torres work “Untitled” (Death by Gun), 1990, this exhibition will be based on research conducted on the gay killings that took place in Sydney in the late 1970s till 2000. This was a period of extreme distrust by the LGBTQI community in the NSW Police Force who symmetrically failed to acknowledge, protect, report, or simply dismiss community concerns. This will result in a series of works highlighting the high number of victims and the fact that a number of murders are unsolved. Although there is conjecture as to whether some of these murders are gay/hate crimes, the fact that were not properly investigated at the time is a dark stain on our history.

What is Strike Force Parrabell?

On 30 August 2015 Strike Force Parrabell commenced a thorough investigative review to determine whether 88 deaths originally listed in a submission to the Australian Institute of Criminology[5], and commonly referred to by media representatives, could be classified as motivated by bias including gay-hate (Strike Force Parrabell 2018).

NOTES

[1] While the onset of HIV/AIDS has been seen as a motivating factor for some of the violence, the start of the violence predates that. A report by the NSW Anti-Discrimination Board in 1982 already highlighted the issue, and over that decade, there was ongoing and increasing violence. In 1990 the Surry Hills police noted a 34% increase in reports of street bashings during that year alone (Wotherspoon 2017).

[2] The Gay and Lesbian Rights Lobby and later, the AIDS Council of NSW (now ACON) kept records, usually comprising self-reported incidents of gay-hate violence, that on several occasions amounted to more than 20 entries per day. Unfortunately, fear associated with anti-gay attitudes of officers within the NSW Police Force at the time prevented these reports being formally recorded, which in turn meant that crimes were not investigated (Strike Force Parrabell 2018, p. 14 & 15)

[3] This inherent lack of consequences or accountability meant that perpetrators were given a kind of ‘social license’ to continue inflicting violence upon members of the gay community. This phenomenon has been associated with what some perpetrators believed was their moral obligation, driven by poor societal expectations. The Bondi incidents together with similar disappearances and deaths of men in and around beats attracted heightened levels of violence and were often associated with a victim’s sexuality or perceived sexuality (Strike Force Parrabell).

[4] During the 1970s, there were ongoing demonstrations in Sydney focusing on what needed to be changed to give homosexuals equal civil rights with their heterosexual counterparts. One of the catchcries of the time was ‘stop police attacks, on gays, women, and blacks’. And this catchcry highlights an important fact: that the police were seen as the enemy by many of these emerging social movements. As for gays, the police had never been sympathetic to their parading through Sydney’s streets. And this antipathy culminated in the notorious first Mardi Gras, on the night of Saturday 24 June 1978; it started out as a peaceful march down Oxford Street from Taylor’s Square to Hyde Park and ended in Kings Cross with police wading into the marchers with their batons, leading to 53 arrests (Wotherspoon 2017).

[5] In 2002, a list of 88 deaths of gay men between 1976 and 2000, potentially motivated by gay hate bias was compiled by Sue Thompson, the then NSW Police Gay and Lesbian consultant. There has been significant media coverage of presumed facts associated with gay hate motivation for each of these 88 deaths.

Reference List

In the Pursuit of Justice. Documenting Gay and Transgender Prejudice Killing in NSW in the Late 20th Century 2017, ACON. viewed 11th November 2018, https://www.acon.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/In-Pursuit-of-Truth-and-Justice-Report-FINAL-220518.pdf.

Kontominas, B 2017, Scott Johnson: Inside one brother’s 30-year fight to find the truth, ABC News, viewed 11 November 2018, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-11-30/scott-johnson-inside-brothers-fight-to-find-the-truth/9211466

Strike Force Parrabell 2018, New South Wales Police Force. viewed November 11 2018, https://www.police.nsw.gov.au/safety_and_prevention/your_community/working_with_lgbtqia/lgbtqia_accordian/strike_force_parrabell

Wotherspoon, G 2017, Gay Hate Crimes in New South Wales from the 1970s, viewed 11th November 2018, https://www.acon.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/In-Pursuit-of-Truth-and-Justice-Report-FINAL-220518.pdf.

The Crisis is not over

Glenn Walls. The crisis is not over. Digital print, 2021. Painting by Jan Davidsz. de Heen, Still Life with Flowers in a Glass Vase. ca. 1650 – 1683. Rijks Museum, Amsterdam.

Glenn Walls. The crisis is not over. Installation view. 2021

Glenn Walls. The lonely crisis is not over. Digital print, 2021.

Glenn Walls. The AIDS crisis is not over. Digital print, 2021. Painting by Jan Davidsz. de Heen, Vase with flowers. ca. 1670.

Super – Perfect Lovers

Super – Overwhelming

Super – Queer City

Glenn Walls. Super – Queer City (Superstudio – The Continuous Monument, 1969). 2020/21. Colour mirror tiles, wheels & mirror plinth.

Glenn Walls. Super – Queer City (Superstudio – The Continuous Monument, 1969). 2020/21. Colour mirror tiles, wheels & mirror plinth.

Glenn Walls. Super – Queer City (Superstudio – The Continuous Monument, 1969). 2020/21. Colour mirror tiles, wheels & mirror plinth.

Glenn Walls. Super – Queer City (Superstudio – The Continuous Monument, 1969). 2020/21. Colour mirror tiles, wheels & mirror plinth.

Glenn Walls. Super – Queer City (Superstudio – The Continuous Monument, 1969). 2020/21. Colour mirror tiles, wheels & mirror plinth.

Glenn Walls. Super – Queer City (Superstudio – The Continuous Monument, 1969). 2020/21. Colour mirror tiles, wheels & mirror plinth.

Super Pride (Superstudio – The Continuous Monument, 1969)

Glenn Walls. Super Pride (Superstudio – The Continuous Monument, 1969). 2020. Colour mirror tiles, skate wheels & mirror plinth.

Installation view at Uro Bookshop at Collingwood Yards. This work was included in the exhibition”A Strange Space” held at Collingwood Yards.

Glenn Walls. Super Pride (Superstudio – The Continuous Monument, 1969). 2020. Colour mirror tiles, skate wheels & mirror plinth.

Installation view at Uro Bookshop at Collingwood Yards. This work was included in the exhibition”A Strange Space” held at Collingwood Yards.

Glenn Walls. Super Pride (Superstudio – The Continuous Monument, 1969). Mirror tiles and skate wheels.

Glenn Walls. Super Pride (Superstudio – The Continuous Monument, 1969). Mirror tiles and skate wheels.

Glenn Walls. Super Pride (Superstudio – The Continuous Monument, 1969). Mirror tiles and skate wheels.

SUPER – THANK YOU

It has been an insane year, but I wanted to send out a massive thank-you to all

you wonderful people who have shown me massive support throughout this year.

Your kindness and generosity has been spectacular and at times genuinely

overwhelming. I am humble by how many of you take the time to read about the work to

gain a better understanding of its purpose. Creating art is a challenge at the best of times.

Creating art that participates in critical discourse focused on queer space, sexuality,

masculinity and the rejection of heteronormative modernist architectural space opens

up an exciting and thought- provoking process that I will continue to develop in 2021.

Thanks to you both LGBTQI+ Persecuted and Pandemic Architecture have sold out.

LGBTQI+ Persecuted is a ongoing series of book covers devoted to queer creatives.

There will be new works coming in 2021.

I am participating in group exhibitions in New York, Sydney and Melbourne in early 2021.

I will keep you posted.

Wishing you all the very best for 2021. xx

Comments Off on SUPER – THANK YOU

Super – I keep dancing on my own

Glenn Walls. I keep dancing on my own. Wood, mirror perspex & paint. 2020

Glenn Walls. I keep dancing on my own + mirror cube. Wood, mirror perspex, paint, mirror tiles and chain. 2020

Comments Off on Super – I keep dancing on my own

Super Mobile (Superstudio: The Continuous Monument 1969)

Glenn Walls. Super Mobile 1 (After Superstudio, The Continuous Monument, 1969). Mirror perspex & skate wheels. 2020

Glenn Walls. Super Mobile 2 (After Superstudio, The Continuous Monument, 1969). Mirror perspex & skate wheels. 2020

Glenn Walls. Super Mobile 3 (After Superstudio, The Continuous Monument, 1969). Mirror perspex & skate wheels. 2020

Glenn Walls. Super Mobile 4 (After Superstudio, The Continuous Monument, 1969). Mirror perspex & skate wheels. 2020

Glenn Walls. Super Mobile 5 (After Superstudio, The Continuous Monument, 1969). Mirror perspex & skate wheels. 2020

Glenn Walls. Super Mobile construction (After Superstudio, The Continuous Monument, 1969). Mirror perspex & skate wheels. 2020

Pandemic Architecture

Glenn Walls. I think we fucked up. (Theo Van Doesburgh, Contra-Construction: project for a private house. Axonometric. 1923). Pencil on paper. 2020. 21 x 29 cms

Pleasure Palaces on the grid. Modernism for the ordinary person

Glenn Walls. Pleasure Palace 1. Biro on paper, 20202. Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, 860 – 880 Lake Shore Drive.

Chicago. 1949 – 1951.

Glenn Walls. Pleasure Palace 2. Biro on paper, 2020. Le Corbusier – Unité d’Habitation, Marseille,

France. 1945

https://lecorbusier-worldheritage.org/en/unite-habitation/

info@marseille-tourisme.com

www.marseille-citeradieuse.org

You /

Glenn Walls: YOU (Stolen Rocks). Mirror perspex, painted rocks. Dimensions variable. 2020

Glenn Walls: YOU (Stolen Rocks). Painted rocks. Dimensions variable. 2020

We don’t embroider cushions here

Glenn Walls. We don’t embroider cushions here. Bauhaus Carpet. Dimensions variable. 2020.

Glenn Walls. All power to you. (Based on Eileen Gray, Rivoli Table, 1928). Steel and wood. Dimensions variable. 2020. Contains Le Corbusier mural that he painted on Gray’s E1027 house between 1938 – 39.

Eileen Gray Vs Le Corbusier

E1027 was the first architectural work of the designer Eileen Gray, completed in 1929 when she was 51 years old. Gray talked of creating “a dwelling as a living organism” serving “the atmosphere required by inner life”. “The poverty of modern architecture,” she said, “stems from the atrophy of sensuality.” She criticised it for its obsession with hygiene: “Hygiene to bore you to death!”

E1027, which was built for Gray and her lover, Jean Badovici, grows from furniture into a building. She created a number of pieces of loose and built-in furniture for the house and installed others that she had previously designed, always with close attention to their interaction with the senses and the human body. She created a tea trolley with a cork surface, to reduce the rattling of cups, another trolley for taking a gramophone outside, and the E1027 table, whose height can be adjusted to suit different situations

Long after Eileen Gray left the villa in 1932, Le Corbusier spent a few days there in 1937, 1938 and 1939. In April 1938, encouraged by Jean Badovici, he painted two murals in the villa and returned the following year to paint another five. He said, “I am dying to dirty the walls: ten compositions are ready, enough to daub the whole lot”. According to her biographers, Eileen Gray didn’t think much of these paintings. In 1949 Badovici threatened to remove them. Several paintings that had been damaged during the war were restored by Le Corbusier himself in 1949 and again in 1963. Three of them, however, have disappeared. Those that have been preserved have since been restored or are under restoration.

Reference: https://capmoderne.com/en/lieu/la-villa-e-1027/ https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2015/may/02/eileen-gray-e1027-villa-cote-dazur-reopens-lost-legend-le-corbusier

Left: Eileen Gray. Rivoli table, 1928.

Glenn Walls. Perfect lovers. (Based on Eileen Gray, Rivoli Table, 1928). Steel and wood. Dimensions variable. 2020.

LGBTQI+. Persecuted.

Glenn Walls. Fierce bitch seeks future ex-husband – David McDiarmid – Lost. Perspex on board. 29 x 42 cms (Book cover). 2019. From David McDiarmid, Rainbow Aphorisms digital print series, 1994.

Glenn Walls. The most common way people give up their power is by thinking they don’t have any – Alice Walker. Perspex on board. 29 x 42 cms (book cover). 2020.

Glenn Walls. For most of history, anonymous was a woman. Virginia Woolf. Cut short. Perspex on board. 29 x 42 cms. (Book cover). 2019.

Glenn Walls. To live is the rarest thing in the world. Most people exist, that is all. Oscar Wilde. Jailed. Perspex on board. 29 x 42 cms (Book cover). 2019.

Glenn Walls. If a bullet should enter my brain, let that bullet destroy every closet door. Harvey Milk. Murdered. Perspex on board. 29 x 42 cms. (Book cover). 2019.

Glenn Walls. LGBTQI+. Persecuted. 9 x Perspex on board. 29 x 42 cms. (Book cover). 2019 – 2020.

Reworking of book covers from my 2012 exhibition “Life Without Objects” held at TCB.

Death by Apple

MASSACRE – BODIES THAT MATTER

KINGS ARI, MELBOURNE

1 December – 20 December 2018

Website: http://www.kingsartistrun.org.au/program/massacre/

In November 2018 I held an exhibition at KINGS ARI on the gay/hate murders that took place in Sydney during the 1970s, 80s, 90s and early 2000 called Massacre.

Link to the exhibition: http://www.kingsartistrun.org.au/program/massacre/

Glenn Walls. Massacre (after Felix). Digital Print on paper stack, 2018. List of the 88 gay/hate murders that took place during the 1970s, 80s, 90s and early 2000s.

Glenn Walls. Massacre (after Felix). Digital Print on paper stack, 2018

Glenn Walls. Lost Sole (Nike sneaker). Jelutong wood (Hand carved), pencil on paper, Mirror plinth. 2018

Glenn Walls. Lost Sole (Nike sneaker). Jelutong wood (Hand carved), pencil on paper, Mirror plinth. 2018

Glenn Walls. Massacre (Disco Glare). Baseball bat, mirror tiles. 2018.

Glenn Walls. Massacre (after Felix). Digital Print on 4 x A3 paper stacks. 2018.

Glenn Walls. Massacre (Disco Glare). Baseball bat, mirror tiles. 2018.

Glenn Walls. Massacre (Disco Glare). Baseball bat, mirror tiles. 2018.

Glenn Walls. Image above & below. Massacre (after Felix). Digital Print on 4 x A3 paper stacks. 2018.

Glenn Walls. Massacre (after Felix). Digital Print on paper stack, 2018

Glenn Walls. Massacre (Disco Glare). Baseball bat, mirror tiles. 2018.

Massacre – Opening 30th November 2018

Kings ARI. 171 King St, Melbourne. Exhibition Dates: 1st December – 21st December 2018

For further details Kings ARI

http://www.kingsartist.run.org.au/program/massacre/

Massacre – Bodies that Matter

‘Our blood runs in the streets and in the parks and in casualty and in the morgue…. ‘Our own blood, the blood of our brothers and sisters, has been spilt too often….

‘Our blood runs because in this country our political, educational, legal and religious systems actively encourage violence against us…

‘We are gay men and lesbians.’

From the ‘One in Seven’ Manifesto, Sydney Star Observer, 5 April 1991

During the 1970s, 80s & 90s in Sydney, Australia a high number of LGBTIQ people were violently bashed, murdered or disappeared entirely. Although some of these incidents were reported in the gay press and the NSW Anti-Discrimination Board[1] at the time many remained unreported to the authorities[2] due to cultural and societal attitudes with and within the NSW police force and the wider community tolerance of homosexuality. With the advent of AIDS in the 80s, “a significant media and social response of gay alienation within the context of ‘moral panic’ occurred” (Strike Force Parrabell 2018, p. 13). ‘Beats’ such as toilet blocks, public parks and beaches (Bondi Headlands) where men met other men for sex or social contact became the target of gangs that felt it was their duty to rid and protect the community of such ‘intolerable’ behaviour [3].

By the late 90s, early 2000s with a growing acceptance within the wider community of homosexuality a series of media reports and research papers emerged within the mainstream press highlighting both the injustice caused to the LGBTIQ community and the entrenched homophobia and failure within the NSW police force that allowed a ‘killing and bashing spree” to take place with little repercussion to the perpetrators[4].

American PhD candidate Scott Johnston was only 27 when he died. “It was December 10, 1988, when Scott’s naked body was found by two rock fishermen at the base of the cliff, near Blue Fish Point, just south of Manly, on Sydney’s northern beaches. Scott’s clothes had been found neatly folded on the clifftop above” (Kontominas 2017) including his pair of Adidas sneakers. This is shown in the exhibition as a wood carving. The police deemed it a suicide. Three months later, Coroner Derrick Hand came to the same conclusion. His brother Steve Johnson and boyfriend of five years, Michael Noone is still today not convinced that this is the case. All failed to acknowledge that the location was a well know beat where anti-gay gangs operated and where other gay/hate murders had occurred previously.

The main research question addressed in this exhibition is:

Through sculptures, architectural models and digital prints, in what ways can I reconfigure the masculine/heterosexual dominance of Superstudio’s anti-design grid to a personal interpretation of queer space?

My reading and understanding of this grid argues a social, philosophical and identity position in which to interpret my works, giving the audience a greater understanding in the power of things to form a narrative for the object or space. My aim is to think through these processes via practice, critiquing Superstudio’s anti-design grid to produce work that re-evaluates masculine/heterosexual dominance of architectural space by highlighting an injustice done to a minority.

Research contribution

Architecture’s preoccupation with ‘normality’ has left little room for queer domestic space to come to the fore. I argue that ‘the “normality” of heterosexuality is so deeply ingrained in Western culture that it is not even seen’ (Myslik 1996, p. 159). So entrenched is this understanding that I have found little evidence of the public acknowledgement of queer space in the built environment, let alone one highlighting queer injustices. Few artists have broached this subject. I am interested in creating a personal definition of queer space that was not hidden and is a reaction against normative symbols of masculinity and the ‘heterosexual assumption’ presented by Superstudio anti-design grid.

Inspired by Cuban artist Felix Gonzalez-Torres work “Untitled” (Death by Gun), 1990, this exhibition will be based on research conducted on the gay killings that took place in Sydney in the late 1970s till 2000. This was a period of extreme distrust by the LGBTQI community in the NSW Police Force who symmetrically failed to acknowledge, protect, report or simply dismissed community concerns. This will result in a series of works highlighting the high number of victims and the fact that a number of murders are unsolved. Although there is conjecture as to whether some of these murders are a gay/hate crime, the fact that were not properly investigated at the time is a dark stain on our history.

What is Strike Force Parrabell?

On 30 August 2015 Strike Force Parrabell commenced a thorough investigative review to determine whether 88 deaths originally listed in a submission to the Australian Institute of Criminology[5], and commonly referred to by media representatives, could be classified as motivated by bias including gay-hate (Strike Force Parrabell 2018).

NOTES

[1] While the onset of HIV/AIDS has been seen as a motivating factor for some of the violence, the start of the violence predates that. A report by the NSW Anti-Discrimination Board in 1982 already highlighted the issue, and over that decade, there was ongoing and increasing violence. In 1990 the Surry Hills police noted a 34% increase in reports of street bashings during that year alone (Wotherspoon 2017).

[2] The Gay and Lesbian Rights Lobby and later, the AIDS Council of NSW (now ACON) kept records, usually comprising self-reported incidents of gay-hate violence, that on several occasions amounted to more than 20 entries per day. Unfortunately, fear associated with anti-gay attitudes of officers within the NSW Police Force at the time prevented these reports being formally recorded, which in turn meant that crimes were not investigated (Strike Force Parrabell 2018, p. 14 & 15)

[3] This inherent lack of consequences or accountability meant that perpetrators were given a kind of ‘social license’ to continue inflicting violence upon members of the gay community. This phenomenon has been associated with what some perpetrators believed was their moral obligation, driven by poor societal expectations. The Bondi incidents together with similar disappearances and deaths of men in and around beats attracted heightened levels of violence and were often associated with a victim’s sexuality or perceived sexuality (Strike Force Parrabell).

[4] During the 1970s, there were ongoing demonstrations in Sydney focusing on what needed to be changed to give homosexuals equal civil rights with their heterosexual counterparts. One of the catchcries of the time was ‘stop police attacks, on gays, women and blacks’. And this catchcry highlights an important fact: that the police were seen as the enemy by many of these emerging social movements. As for gays, the police had never been sympathetic to their parading through Sydney’s streets. And this antipathy culminated in the notorious first Mardi Gras, on the night of Saturday 24 June 1978; it started out as a peaceful march down Oxford Street from Taylor’s Square to Hyde Park, and ended in Kings Cross with police wading into the marchers with their batons, leading to 53 arrests (Wotherspoon 2017).

[5] In 2002, a list of 88 deaths of gay men between 1976 and 2000, potentially motivated by gay hate bias were compiled by Sue Thompson, the then NSW Police Gay and Lesbian consultant. There has been significant media coverage of presumed facts associated with gay hate motivation for each of these 88 deaths.

Reference List

In the Pursuit of Justice. Documenting Gay and Transgender Prejudice Killing in NSW in the Late 20th Century 2017, ACON. viewed 11th November 2018, https://www.acon.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/In-Pursuit-of-Truth-and-Justice-Report-FINAL-220518.pdf.

Kontominas, B 2017, Scott Johnson: Inside one brother’s 30-year fight to find the truth, ABC News, viewed 11 November 2018, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-11-30/scott-johnson-inside-brothers-fight-to-find-the-truth/9211466

Strike Force Parrabell 2018, New South Wales Police Force. viewed November 11 2018, https://www.police.nsw.gov.au/safety_and_prevention/your_community/working_with_lgbtqia/lgbtqia_accordian/strike_force_parrabell

Wotherspoon, G 2017, Gay Hate Crimes in New South Wales from the 1970s, viewed 11th November 2018, https://www.acon.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/In-Pursuit-of-Truth-and-Justice-Report-FINAL-220518.pdf.

Philip Johnson

Glenn Walls. Philip Johnson. Pencil on Paper. 2018

Glenn Walls. Philip Johnson. Pencil on Paper. 2018

National Pride

Glenn Walls. National Pride – Indigenous Flag. Acrylic Perspex. 59 cms diameter, 2017.

“Tell him he’s dreaming” is taken from the 1997 Australian movie, “The Castle”.

Why Bother

Why Bother. (Woman’s Nike Sky Dunk Hi Essential). Jelutong wood, mirror perspex, yellow paint. 2017

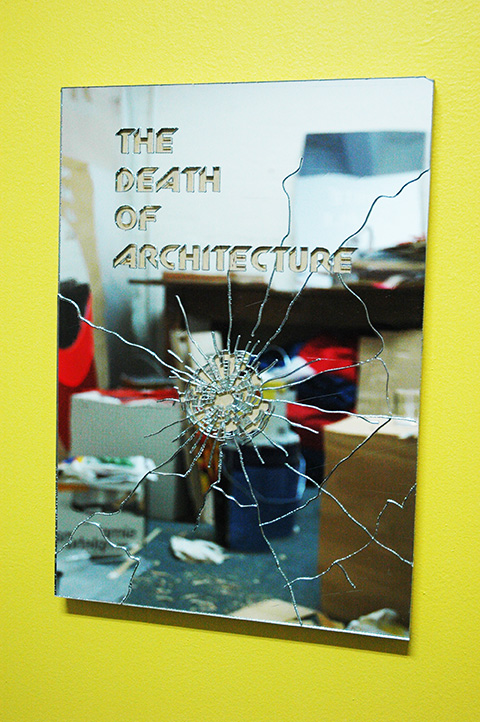

The Death of Architecture (Superstudio: The Continuous Monument)

Glenn Walls. The Death of Architecture (Inspired by Superstudio, The Continuous Monument). Metal staples & Skateboard wheels. 2016

Glenn Walls. The Death of Architecture (Inspired by Superstudio, The Continuous Monument). Metal staples & Skateboard wheels. 2016

Glenn Walls. The Death of Architecture (Inspired by Superstudio, The Continuous Monument). Metal staples & Skateboard wheels. 2016

Glenn Walls. The Death of Architecture (Inspired by Superstudio, The Continuous Monument). Metal staples & Skateboard wheels. 2016

Superstudio, The Continuous Monument. Never constructed 1969 – 71

Superstudio, The Continuous Monument. Never constructed 1969 – 71

On top of the world… Il Monumento Continuo, a gridded structure that the Superstudio architects suggested would eventually cover the planet (Glancey, J. 2003).

The Death of Architecture (Part 4)

The Death of Architecture (Part 4) . Based on Superstudio, The Continuous Monument. Mirrors, mirrored perspex on wood, skater wheels

The Death of Architecture (Part 4) Mirrored perspex on wood.

The Death of Architecture (Part 4) Mirrored perspex on wood.

The Death of Architecture (Part 3)

The Death of Architecture (Part 3). Mirror perspex, Jelutong and wool rug

The Death of Architecture (Part 3). Development work. Jelutong

The Death of Architecture (Part 3). Development work. Jelutong

The Death of Architecture (Part 3). Development work. Jelutong

leave a comment